Universal Design of Physical Spaces

This section of The Center for Universal Design in Education focuses on how we can apply universal design (UD) to create spaces that are accessible, usable, and inclusive.

Modifying the basic definition of universal design (UD) of the Center for Universal Design only slightly, the UD of physical spaces can be defined as “the design of physical spaces to be usable by all people, to the greatest extent possible, without the need for adaptation or specialized design.” The seven principles of UD are as follows:

- Equitable use. The design is useful and marketable to people with diverse abilities.

- Flexibility in use. The design accommodates a wide range of individual preferences and abilities.

- Simple and intuitive. Use of the design is easy to understand, regardless of the user's experience, knowledge, language skills, or current concentration level.

- Perceptible information. The design communicates necessary information effectively to the user, regardless of ambient conditions or the user's sensory abilities.

- Tolerance for error. The design minimizes hazards and the adverse consequences of accidental or unintended actions.

- Low physical effort. The design can be used efficiently, comfortably, and with a minimum of fatigue.

- Size and space for approach and use. Appropriate size and space is provided for approach, reach, manipulation, and use regardless of the user's body size, posture, or mobility.

For the process of applying UD to physical spaces and other introductory material, read Equal Access: Universal Design of Physical Spaces.

See concrete examples of practices that apply each principle of UD by touring Berkeley, California's universally designed Ed Roberts Campus by watching the short video The 7 Principles of Universal Design.

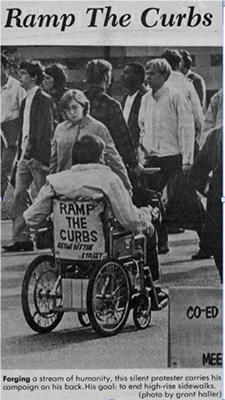

The application of UD is not new with respect to the physical environment. Back in the 1970s, advocates pushed for curb cuts in sidewalks to make them accessible to wheelchair users. In an article that appeared in the UW Daily in 1970, a young man wore a sign on the back of his wheelchair, "Ramp the curbs. Get me off the street." Now curb cuts are ubiquitous and we recognize that curb cuts benefit many people—parents pushing baby strollers, delivery staff pushing carts, skate boarders (not necessarily a good thing).

As with other applications of UD, physical spaces that are universally designed exhibit three characteristics. They are accessible, usable, and inclusive.

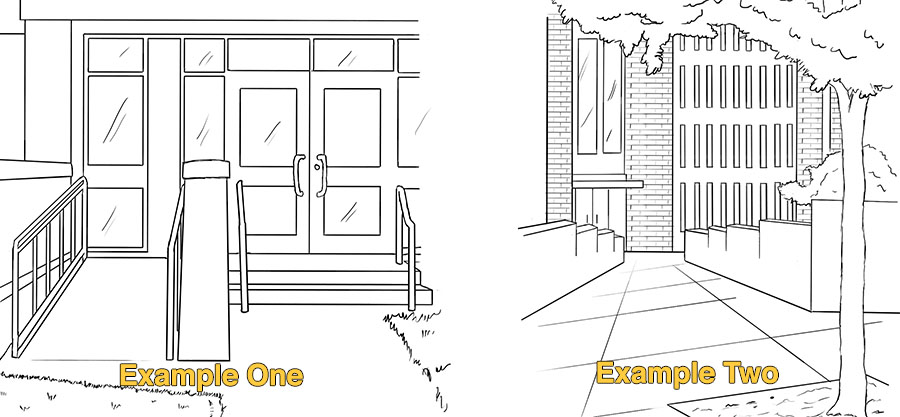

The image below presents two examples of entrances: Example One features two steps for the entrance directly to the door or the alternative, a ramp to the side of them. This arrangement complies with the Americans with Disabilities Act, providing an arrangement that is both accessible and usable. Example Two features an entrance that is universally designed. It is accessible and usable for everyone but exhibits the third characteristic of UD—it is inclusive because all individuals can enter the same way, using the wide, gently sloping ramp. When I walk into this space with a companion using a wheelchair, we can enter side by side.

As far as interior spaces, the following two images show different angles of a service counter in the DO-IT Center at the University of Washington. Its multiple-height design is accessible and usable by staff and visitors of different heights and engaging from a standing or seated position.

The DO-IT Center also offers many printed resources that visitors can browse and take for free. These resources are positioned on a wall where they can be reached from a seated or standing position.

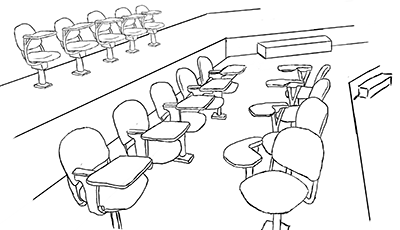

As an example of a classroom application of UD, the image below shows rows of desks in an auditorium where the chairs spin around, making it easier to conduct one-to-one and small group discussions in class. There is also spaces provided on multiple levels for people in wheelchairs to participate. It illustrates the importance of developing physical spaces that are flexible in their use.

There are a variety of other educational settings, including labs and makerspaces. Review the publications below to find more options for universally designing physical spaces.

DO-IT Publications

The following DO-IT publications provide examples of how to create inclusive physical spaces in educational settings.

- Equal Access: Universal Design of Physical Spaces

- Making a Makerspace? Guidelines for Accessibility and Universal Design

- Making Science Labs Accessible to Students with Disabilities

- Checklist for Making Science Labs Accessible to Students with Disabilities

- Facilitating Accessibility Reviews of Informal Science Education Facilities and Programs

- Equal Access: Universal Design of Computer Labs

- Checklist for Making Computer Labs Accessible to Students with Disabilities

- Checklist for Making Engineering Labs Accessible to Students with Disabilities

Articles and Book Chapters

AccessEngineering. (2017). Equal access: Universal design of engineering labs. Seattle: DO-IT, University of Washington.

AccessEngineering. (2015). Making a makerspace? Guidelines for accessibility and universal design. Seattle: DO-IT, University of Washington.

Alper, M. (2014). Making space in the makerspace: Building a mixed-ability maker culture. <>University of Southern California Los Angeles.

Axelrod, J. (2014). Universal design in built and online environments. Beyond the Americans with Disabilities Act: Inclusive Policy and Practice for Higher Education (pp.141-144). NASPA-Student Affairs Administrators in Higher Education.

Burgstahler, S. (2020). Physical spaces. Creating Inclusive Learning Opportunities in Higher Education: A Universal Design Toolkit (pp. 57–72). Harvard Education Press.

Burgstahler, S. (2015). Universal design of physical spaces: From principles to practice. Universal design in higher education: From principles to practice (pp. 201-213). Harvard Education Press.

Burgstahler, S. (2017). Equal access: Universal design of housing and residential life. Seattle: DO-IT, University of Washington.

Goldstein, E. (2015). Applications of universal design to higher education facilities. Universal design in higher education: From principles to practice, 215-228.

Hamraie, A. (2017). Building access : Universal design and the politics of disability. University of Minnesota Press.

Hamraie, A. (2013). Designing collective access: A feminist disability theory of universal design. Disability Studies Quarterly, 33. http://dx.doi.org/10.17613/M6T98Q

Hamraie, A. (2016). Universal design and the problem of "post-disability" ideology. Design and Culture, 8(3), 285-309.

Klipper, B. (2014). Making makerspaces work for everyone: Lessons in accessibility. Children and Libraries, 12(3), 5–6.

Meyer, A., & Fourie, I. (2016). Make the makers’ voices count: Combining universal design and participatory ergonomics to create accessible makerspaces for individuals with (physical) disabilities. In proceedings from EAHIL '16: European Association for Health Information and Libraries. Seville, Spain.

Null, R.L., & Cherry, K.F. (1996). Universal design: Creative solutions for ADA compliance. Professional Publications.

Persson, H., Ahman, H., Yngling, A. A., & Gulliksen, J. (2014). Universal design, inclusive design, accessible design, design for all: Different concepts—one goal? On the concept of accessibility—historical, methodological and philosophical aspects. Universal Access in the Information Society, 14(4), 505-526.

Burgstahler, S. (2012). Making science labs accessible to students with disabilities. Seattle: DO-IT, University of Washington.

<>Sholanke, A., Adeboye, A., Oluwatayo, A., & Alagbe, O, (2016). Evaluation of universal design at the main entrance of selected public buildings in Covenant University. Covenant University International Conference on African Development Issues (CU-IADI), Ota, Ogun State, Nigeria, 3, 188–192.

Smyser, M. (2003). Maximum mobility and function. American School & University.

Staeger-Wilson, K., & Sampson, D. H. (2012). Infusing just design in campus recreation. Journal of Postsecondary Education and Disability, 25(3), 247-252.

Steinfeld, E., & Maisel, J. (2012). Universal design: Creating inclusive environments. J. Wiley & Sons.

Story, M. F., Mueller, J. L., & Mace, R. L. (1998). The universal design file: Designing for people of all ages and abilities. Raleigh, NC: Center for Universal Design, North Carolina State University.

Sweet, E. (2018). Accessibility in the laboratory. ACS Symposium Series, 1272. http://www.doi.org/10.1021/bk-2018-1272.ch001

Thompson, T. (2008). Universal design of computing labs. Universal design in higher education: From principles to practice, 235-244.

<>Watson, E., Bartlett, F., Sacks, C., & Davidson, D. L. (2013). <>Implementing universal design: A collaborative approach to designing campus housing. Journal of College & University Student Housing, 39(40), 158–171.

Wilkoff, W., & Abed, L. (1994). Practicing universal design: An interpretation of the ADA. Van Nostrand Reinhold.

Wisbey, M. E., & Kalivoda, K. S. (2003). Residential living for all: Fully accessible and “liveable” on-campus housing. Curriculum transformation and disability: implementing universal design in higher education (pp. 255-266). University of Minnesota.